Several different Pythium spp. cause them. P. irregulare and P. ultimum are the most common in Western Canada. Like Aphanomyces, Pythium is an oomycete that produces long-lived oospores, allowing the disease to persist in soil until conditions are favourable for germination.

Pythium spp. prefer cold, wet, saturated soils and can infect host crops like peas and lentils when growing conditions cause slow-growing seedlings.

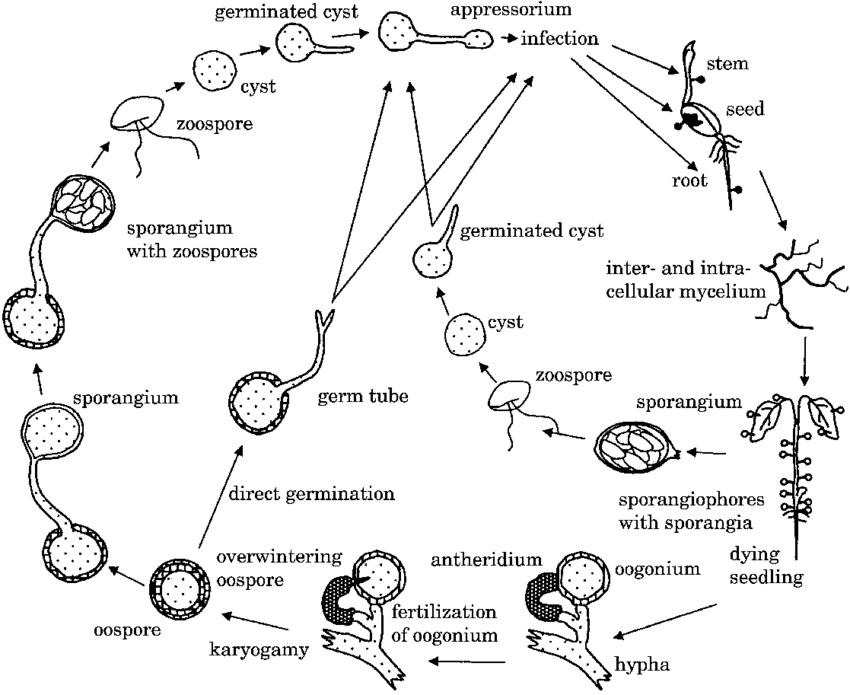

Both Pythium irregulare and Pythium ultimum are water mould pathogens that begin their life cycle with the formation of oospores, which are thick-walled and hardy spores. These oospores allow the fungi to survive in harsh conditions, such as dry periods or cold weather, by remaining dormant in the soil for long periods until favourable conditions arise.

The oospores germinate when environmental conditions improve, such as with increased moisture and suitable temperatures. This germination process involves the oospore breaking open and producing a germ tube. The germ tube then develops into hyphae, thread-like structures that grow and spread in the soil. These hyphae come into contact with plant roots or seedlings and penetrate the plant tissue, starting an infection. Inside the plant, the hyphae continue to grow, causing damage to the plant cells. This can lead to symptoms like root rot, damping-off in seedlings, and overall poor plant health.

As the fungi grow, they can produce asexual spores called sporangia, which release motile spores known as zoospores. These zoospores can swim in water and infect new plants by reaching their root systems. Additionally, Pythium species can reproduce sexually by forming new oospores when two different mating types come together, ensuring genetic diversity. This cycle allows Pythium irregulare and Pythium ultimum to persist in the environment and continuously infect new plants, leading to recurring plant diseases.

Symptoms

Seed rot—when removed from the soil, they emerge with a layer of soil around them (full of whitish, threadlike fungal hyphae).

Cracked seed coats allow Pythium to infect planted seeds, resulting in rotten, mushy seeds or seedlings. Germinating seeds are only susceptible for 48 to 72 hours—once the root emerges, the seed is no longer vulnerable to infection (new developing tissue, however, remains susceptible). Emerging plants and roots, if produced, may be soft and watery; cotyledons may or may not rot. Infected roots are light brown and gelatinous in texture, causing seedlings to dampen off.

Pythium infections can also occur at the tip of feeder roots, where young tissue can be destroyed, leading to root pruning and a reduction in length. Depending on the severity of the infection, seedlings may become stunted and chlorotic and collapse as the root base decays and turns tan to light brown. Later in the season, infection can destroy lateral feeder roots and brown discoloration of the tap root. The outer root tissue is quickly stripped away.

Symptoms may resemble Phytophthora and can appear scattered throughout the field.

Resources

No current resources are directly focused on Pythium; however, the following resources provide general guidance on root rot pathogens.

Aphanomyces Root Rot in Pulse Crops | Saskatchewan Pulse Growers

Aphanomyces Root Rot in Peas and Lentils in Western Canada, 2019 | Alberta Pulse Growers

Root Rot in Peas and Lentils in Western Canada, 2016 | Manitoba Pulse & Soybean Growers

Research Keeping Up the Fight Against Aphanomyces | Alberta Pulse Growers